How to Smuggle Vegetables Into North Korea Huffington Post Edition: US 01/26/2016 05:17 pm ET | Updated Jan 26, 2016

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rachel-stine/how-to-smuggle-vegetables_b_9075078.html

Rachel Stine has worked with North Korean refugees for six years. Today, she lives in Seoul, where she writes about traditional culture and politics.

Reverend Timothy Peters wears wire-framed glasses, a button-down shirt, and a bright smile. At first glance, one might imagine him teaching at an Ivy League university. But beneath his jovial, academic exterior, you will find an iron-willed activist. In 2006, Reverend Peters’ was featured on the cover of Time Asia alongside the words: “Seoul Saver.” He serves as one of the major conductors on Asia’s great underground railroad, which spans across the continent and helps North Koreans escape to free countries. In 2015 alone, his NGO, Helping Hands Korea, helped 120 escapees obtain amnesty.

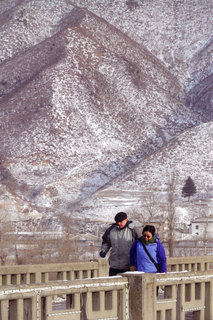

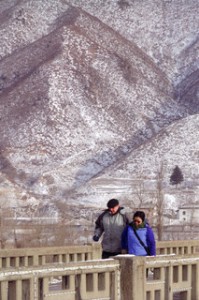

Tim and his wife, Sunmi, stand on a Chinese bridge with North Korea in the background.

Tim and his wife, Sunmi, stand on a Chinese bridge with North Korea in the background.

Reverend Peters’ latest project, however, aims to impact more lives. Rather than just spiriting a trickle of refugees to freedom abroad, he is also smuggling nutrient-rich vegetable seeds into North Korea, in a bold effort to provide food security for the 24.9 million people still trapped behind its barbed wire borders.

This campaign comes at a critical time. Due to some minor land reforms in the North, rural families now are allowed to cultivate tiny plots of land privately. A China-based refugee explained to him: “We have the land now, but we don’t have seeds.”

“When she said that, I knew we were on the right track,” Tim said. “I believe we were providentially led in this direction.”

The Seed Project began in summer of 2015, when a member of Reverend Peter’s activist group, Catacombs, returned from a visit to her family farm in Michigan. She brought vegetable seeds to Seoul, thinking it would be a lightweight and discreet way to send food aid into North Korea.

Reverend Peters recalled of that time: “We sent the first batches into North Korea using various networks. Soon after that, another Catacombs member, Ed, mentioned that his grandfather bequeathed to him a chestnut orchard some time ago. I half-jokingly said: ‘Ed, are all those chestnuts just rotting on the ground when you’re over here in Korea?’ The next thing I knew, his family had sent a big box of seeds from America as a donation to our initiative. That is how The Seed Project began.”

Catacombs volunteers — a motley assortment of graduate students, English teachers, military personnel, and local high school students — now gather weekly at a small art gallery. Their goal is to repackage high-quality vegetable seeds with Korean planting instructions, while keeping up-to-date on the latest North Korea headlines. This winter, they have prepped over one thousand units.

Food security is still a problem in the North, where the United Nations estimates that 31% of citizens are undernourished. Through volunteer work, Catacombs members hope to slash those numbers. The strategy is effective especially in rural provinces, where people tend to be poor, but equipped with basic agricultural skills.

Attendees spend about two hours a week hunched over two round-top tables. As they repackage seeds, there is a lively buzz of conversation over trays of cookies and hot tea. In one corner, a graphic novelist and an illustrator discuss their latest publications. While scooping seeds from a Daiso container, a Fulbright scholar and PhD candidate quietly lament the tribulations of academics. English teachers at another table recommend EFL songs from YouTube for use in their classes. Around 9 P.M., the conversation quiets as Reverend Peters closes with a group prayer.

Despite the religious nature of Peters’ approach, Catacombs enjoys significant support from human rights activists on the secular left. At any given meeting, a third of the attendees are atheist or agnostic. Included in this demographic is regular attendant Craig Urquhart. A Canadian activist, Craig recently donated approximately 100 packets of organic, heirloom seeds designed to grow well in frosty climates.

“It’s not like we’re sending Bibles North,” he said. “We’re sending seeds – food – and a path to a better future. Sending seeds North is one way to help North Koreans who suffer repression by their government. It slightly reduces their dependence on the state dictatorship and it fosters food independence. There’s no negative to this kind of engagement.”

Kurt Achin, a Seoul-based journalist and Catholic supporter of the program, remarked: “I met Tim in 2004 when I came over here to report on defectors and human rights. I am a huge supporter of his quiet approach.”

“The quiet approach” refers to the manner in which Helping Hands Korea has used only a very basic website to create a substantial movement. Despite having no social media presence, they have one of the rescue rates of any registered nonprofit organization. Since 2014, they have helped over 220 North Koreans leave dangerous situations. Reverend Peters has plans to expand The Seed Project over the course of this year, by boosting donations and increasing the number of repackaging workshops.

“We are very excited about this project,” Reverend Peters said. “We are building on the lessons Helping Hands Korea has learned during our twenty years of helping North Koreans in crisis, operating outside of the Kim regime’s structures to reach the most vulnerable. We will continue to maximize ‘trickle-down’ dynamics in our deliveries of vegetable seeds. This will have a deeply positive impact on North Korean families. The enthusiasm and active ‘roll-up-your-sleeves’ participation in the seeds initiative by young people – Koreans and expats alike – is a huge encouragement. The torch is being passed to a new and very capable generation.”